Think you’re worried about the coronavirus? In Episode 128, Jeff Belanger and Ray Auger explore Hospital Rock deep in the woods of Farmington, Connecticut. In the 1790s this was the site of a smallpox inoculation hospital. Smallpox was a plague that wiped out families and communities. Hundreds of people in the region came here for treatment, but 66 left their names etched in the stone as a testament to a plague.

CALL (OR TEXT) OUR LEGEND LINE:

(617) 444-9683 – leave us a message with a question, experience, or story you want to share!

BECOME A LEGENDARY LISTENER PATRON:

https://www.patreon.com/NewEnglandLegends

CREDITS:

Produced and hosted by: Jeff Belanger and Ray Auger

Edited by: Ray Auger

Additional Voice Talent: Michael Legge

Theme Music by: John Judd

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST FOR FREE:

Apple Podcasts/iTunes | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | TuneIn | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | SoundCloud

JOIN OUR SUPER-SECRET:

New England Legends Facebook Group

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

*A note on the text: Please forgive punctuation, spelling, and grammar mistakes. Like us, the transcripts ain’t perfect.

[RAY COUGHING]

JEFF: You feeling okay, Ray?

RAY: Yeah, Jeff. Just getting over a cold.

JEFF: You sure it’s not that coronavirus from China?

RAY: Dude, don’t freak me out. It’s just a cold, not some horrible epidemic!

JEFF: That’s the crazy thing about viruses, they mutate all the time. Sometimes they can be mild and pass right through a community unnoticed, other times there can be deadly outbreaks that make international news.

RAY: I know what you mean! Ebola, swine flu, now the coronavirus, you hear about so many outbreaks, it’s a scary world out there.

JEFF: There was a time when outbreaks truly devastated local communities. And that’s why we’re hiking in the woods near Rattlesnake Mountain in Farmington, Connecticut, today. We’re searching for a relic of a plague. We’re looking for hospital rock.

[INTRO]

JEFF: Hey, I’m Jeff Belanger.

RAY: And I’m Ray Auger, and welcome to episode 128 of the New England Legends podcast. If you give us about ten minutes, we’ll give you something strange to talk about today.

JEFF: Thanks for joining us on our mission to chronicle every legend in New England one story at a time. And we can’t do that without our patreon patrons who kick in $3 bucks per month.

RAY: That’s less than the price of one draft beer per month!

JEFF: They help us with our hosting and production costs. Head over to patreon.com/newenglandlegends to sign up for bonus episodes and content that no one else gets to hear.

[HIKING IN WOODS]

RAY: Okay, so we’re hiking in the woods of Farmington looking for a rock?

JEFF: A big rock, Ray. It’s located just off the Metacomet Trail.

RAY: What’s so special about this rock?

JEFF: It’s covered in names carved into the stone. It’s a large, flat exposed rock.

RAY: Hey, check this out over there.

JEFF: Yeah, I think that’s it!

RAY: Okay, it’s big, mostly close to the ground, more like a bald hilltop. It’s maybe 20 feet by 15 feet or so.

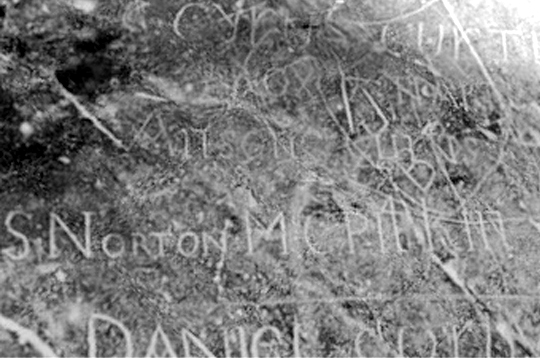

JEFF: And if you look up close, you can see there are a bunch of names carved into the rock.

RAY: Oh yeah! I see the name Carl, James, some are too faint to read. But there’s a bunch here.

JEFF: To figure out how this antique graffiti got here, we’re going to head back to 1792 and set this up.

[TRANSITION]

JEFF: It’s 1792 here in Farmington, Connecticut. George Washington is president, and the United States is still very much a new country. It’s an exciting time, but also a scary one as well.

RAY: There’s nothing but potential and possibilities for the country, but that’s also frightening because there’s no support from anywhere else. We’re on our own.

JEFF: The British have been defeated and are gone, but there are other enemies we still have to worry about. Enemies so small that you can’t even see them. Locals may not be too concerned about Redcoats anymore, but they’re petrified of smallpox.

RAY: Smallpox. For help with what it is, we’d like to consult a local Farmington medical expert. Dr. Eli Todd, can you please weigh in on this?

DR TODD: Of course! Smallpox is known in the medical community as the variola virus. It’s carried only by humans, and it has a long incubation period, which unfortunately means an infected person can spread the virus before they even realize they’re sick.

JEFF: What happens to a person infected with smallpox?

DR TODD: The illness begins with a high fever and an achy body, similar to the flu. But then a rash forms in the mouth. It starts as small bumps. Over the span of approximately four days, those bumps turn to sores, then break open, spreading the virus even further. Next, a rash appears on the skin, starting with the face, then spreading to the arms and legs, then on to the hands and feet. Those sores… or pustules… then fill with fluid that can burst open. If the patient doesn’t succumb to the virus, those pustules eventually turn to scabs and then fall off. The illness can last up to 12 weeks and the overall mortality rate is 30%, but of course those rates are much higher in children and the elderly.

JEFF: There’s a saying around New England these days that your child is not your own until he survives smallpox.

RAY: Wow, that’s grim.

JEFF: The mortality rate in children is huge. So if you’re lucky, you have smallpox for about six-to-twelve weeks until the virus leaves your body and you’re no longer contagious. And given those bursting pustules on a sick person, this virus spreads quickly. The virus can contaminate a blanket, and spread to another person through almost any kind of contact. It’s really frightening. But the good news is, once you’re exposed and build an immunity, you won’t get it again.

RAY: Vice President John Adams has called smallpox quote “The King of Terrors,” and medical textbooks refer to the virus as quote “the most loathsome and fatal disease known to man.” This IS scary stuff. So what do we do about this terrible virus?

JEFF: The best we can do is quarantine the sick as soon as soon as there’s a breakout. Or inoculate the healthy. And this is important, because there’s an outbreak happening in Farmington right now. An outbreak that’s taking lives. We should tell you a little more about our medical expert, doctor Eli Todd from New Haven.

RAY: Eli Todd is the son of a New Haven merchant and a Yale graduate. By age 21, he opened his own medical practice here in Farmington and though he’s young, he’s quickly building a good reputation as a kind and gentle doctor during a time when harsh treatments are the norm.

JEFF: When the smallpox outbreak hits Farmington in 1792, someone has to do something. So two local doctors, Eli Todd and Theodore Wadsworth appear before the Farmington town council to get permission to setup a for-profit smallpox hospital on a wooded parcel of land donated by Farmington resident Elias Brown.

[GAVEL BANGING ON BENCH]

JEFF: The motion is passed, and the two get to work setting up their inoculation clinic in the woods on a stony hillside known as goat pasture off of Settlement Road. Rattlesnake Mountain provides a natural block to the north wind that might otherwise chill the patients.

RAY: Doctors have figured out that if a person is exposed to a small dose of a virus, they can build up an immunity to it. An immunity that can save their life and the lives of people in their community. So doctors Todd and Wadsworth have several buildings constructed on this site in the woods.

[HAMMERING AND SAWING]

RAY: In the autumn, they’re ready to receive patients. You have to realize that this is a for-profit clinic. So the patients are people who can afford to come here for three weeks and get treatment. This is really a kind of medical resort. Not the fanciest place in the world, but still, it’s not bad.

JEFF: Okay, let’s go inside and watch Dr. Todd perform an inoculation on a patient.

[DOOR OPENING]

RAY: Oh look, the patient is 26-year-old Abigail Scott. She’s a local girl.

JEFF: Okay, there’s a man sitting here who is covered in smallpox sores.

RAY: Dr. Todd is using a scalpel to slice open one of those sores. Ugh… it’s oozing some kind of puss.

JEFF: Now the doctor is running a small piece of thread through the puss.

RAY: Oh man, I could never be a doctor. This is gross. Now doctor Todd is cutting a small incision on the arm of Abigail Scott. She’s bleeding, but just a little bit.

RAY: Okay, he’s running that puss-covered string through Abigail’s cut… Back and forth.

JEFF: And now he’s applying a small bandage. That’s it, doctor?

DR TODD: That’s it.

JEFF: Abigail will now have to stay here for about three weeks. She’s expected to go through some of the smallpox symptoms on a more mild scale while her body builds up an immunity.

RAY: Sitting around for three weeks can be tough. Under no circumstances can Abigail or any of these other patients leave because they could expose others to smallpox. So these patients are stuck. If their symptoms are really mild, this stay can get really boring.

JEFF: A facility like this also needs supplies like food and water. They need blankets. And the patients need letters and gifts from home while they wait out smallpox. So let’s take a walk.

[WALKING THROUGH THE WOODS]

JEFF: If we head out about a hundred yards in this direction, we’ll find a large rock near a stagecoach road.

[HORSES STAGECOACH GOING SLOW]

RAY: And here it is! This is the place those supplies and letters are dropped off so there’s no contact with the patients, but they can still receive letters.

JEFF: If you look at the nearby rock, it’s already getting covered with the carvings of names.

RAY: This one says: J. Bronson, discharged from smallpox hospital September 1792. Age 10 years.

JEFF: There’s one that says Nathan North, 15, 1794.

RAY: And look! Here’s Abigail Scott’s name. Age 26, 1794.

JEFF: Over the years, hundreds of people came here to the Todd-Wadsworth Smallpox Hospital. On days they felt well, they might sun themselves on this rock as they wait for mail and supplies from home. And 66 of them had their names and inscriptions chiseled onto the rock.

RAY: Why do you think they had their names chiseled here?

JEFF: I can think of two reasons. One is that we have a natural tendency to leave our mark on places we’ve been. Cavemen did it with paintings and etchings, prisoners do it in dungeons and jails, and these patients did it as well. Kind of a: hey look, I was really here.

RAY: What’s the other reason?

JEFF: I wonder if all of these names served as a kind of testimonial billboard for Todd and Wadsworth?

RAY: Ohhhh I get it. If you come here to drop off supplies you see all of these names of patients once treated right here. Maybe you tell others that this is the place to go for smallpox inoculations.

JEFF: And if you’re a patient, here’s dozens of names of people successfully treated so you feel good about how you spent your money. And that brings us back to today.

[TRANSITION]

RAY: Obviously these engravings happened centuries before HIPPA.

JEFF: Obviously.

RAY: Jeff, I can’t help but wonder, are we safe after having witnessed that smallpox inoculation up close like that?

JEFF: The short answer is no. We’re not safe, and the reason is neither one of us received the smallpox vaccine as kids because in the United States they stopped vaccinating for smallpox in 1972 because the virus was considered eradicated.

RAY: I did a little digging. The very first smallpox vaccine was discovered in 1796. A British doctor named Edward Jenner discovered that milkmaids who were exposed to cowpox were somehow immune from smallpox.

JEFF: So the viruses must be just similar enough that antibodies for cowpox will fight off smallpox.

RAY: Inoculation methods continue to improve over the decades until it’s discovered that injecting a dead form of the virus into a person will cause them to build up antibodies and an immunity the same as if you really got sick, and suddenly the days of vaccines were born. Vaccines that have saved millions and millions of lives to the point were smallpox was considered eradicated in the United States back in 1972.

JEFF: There’s also a dark side to viruses like smallpox.

RAY: You mean besides getting sick and dying?

JEFF: Yeah. If that isn’t dark enough, smallpox has the unfortunate distinction of being the first biological weapon. In the late 1700s, blankets used by smallpox patients were distributed to Native American groups with the expressed intent of causing an outbreak. The weapon worked, killing roughly 50% of the affected tribes.

RAY: That’s horrible.

JEFF: It is.

RAY: And of course it could happen again.

JEFF: Especially if large percentages of the population lose immunities to various viruses and diseases.

RAY: Imagine being taken out by some foreign power who only uses a blanket for a weapon?

JEFF: Or contaminated bottled water? Or clothes? Or food? Yeah. Scary.

RAY: I’m glad I’m up-to-date on my shots.

JEFF: And I’m glad Hospital Rock is still here. Sure it’s fading into nothing, but it’s a reminder of a time when plagues really did wipe out communities. And 66 people had their names etched here maybe in the hopes that we won’t forget, and won’t let it happen again.

[OUTTRO]

RAY: It’s funny how a story like this can feel like it’s both ancient history and ripped from today’s headlines. I wonder if centuries from now someone will tell a story like this about the coronavirus, or AIDS, or some other epidemic?

JEFF: That’s the power of a legend. It’s still relatable, so we keep it around.

RAY: And we want you guys to keep us around. If you don’t already subscribe to our podcast you should because it’s free! You can find us on iTunes, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, TuneIn, SoundCloud, or wherever you get your podcasts.

JEFF: And please do us a favor. If you enjoy our show, tell a friend or two about us. Or post about us on social media. Or join our super secret Facebook group. You can find links on our Web site: ournewenglandlegends.com

RAY: We’d like to thank Michael Legge for lending his voice acting talents this week, and our theme music is by John Judd.

VOICEMAIL: Hi this is Kathleen from Pure, Michigan. Until next time remember… the bizarre is closer than you think.

Copyright © 2020 New England Legends. All rights reserved.