In Episode 329 Jeff Belanger and Ray Auger spend Christmas strolling the grounds of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s former mansion in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to witness the birthplace of a poem written Christmas morning in 1863, when Longfellow felt his hope renewed after his son had been badly injured in a Civil War battle. The poem was later turned into a holiday song that’s been recorded by giants like: Burl Ives, Frank Sinatra, Harry Belafonte, Andy Williams, and Johnny Cash.

BECOME A LEGENDARY PATRON:

https://www.patreon.com/NewEnglandLegends

CREDITS:

Produced and hosted by: Jeff Belanger and Ray Auger

Edited by: Ray Auger

Guest Voice Talent: Marv Anderson

Theme Music by: John Judd

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST FOR FREE:

Apple Podcasts/iTunes | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | Amazon Podcasts | TuneIn | iHeartRadio

JOIN OUR SUPER-SECRET:

New England Legends Facebook Group

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

*A note on the text: Please forgive punctuation, spelling, and grammar mistakes. Like us, the transcripts ain’t perfect.

[CHURCH BELLS]

[CITY STREETS]

RAY: There’s something about hearing church bells in late December here in chilly Cambridge, Massachusetts, that makes me think of Christmas.

JEFF: I agree. The peal of the bells seems to pierce the cold and warm the heart. It reminds me of that Leonard Cohen song, “Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

RAY: Thank God we have the poets like Leonard Cohen.

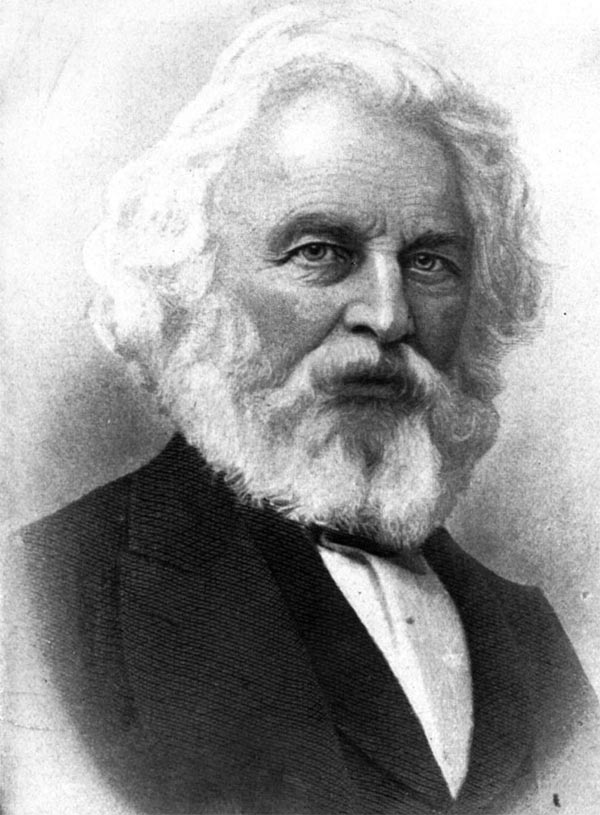

JEFF: Thank God indeed. Sometimes we need the poets to express what we’re all feeling. Seeing that it’s our Christmas special, I thought we’d come to Cambridge to hear the bells that inspired one of the greatest poets, not just in New England History, but American history. This is the old stomping ground of none other than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

RAY: He’s a giant for sure. His name is sacred in Massachusetts.

JEFF: One of his poems was turned into a Christmas song. Maybe not the most famous Christmas song of all time, but some of the holiday giants like Burl Ives and Frank Sinatra included their own versions of the song on their holiday albums. And The Civil Wars have a haunting version of the song that’s becoming one of my new favorites. But the lyrics most of us have heard leaves out the darkest part of the story.

RAY: There’s always an undertone of darkness in Christmas, isn’t there?

JEFF: I’ve been saying for a while now, you need to get into a dark place if you’re going to see the light. We’ve come to Cambridge at Christmas to explore the story behind Longfellow’s poem “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day.”

[INTRO]

JEFF: I’m Jeff Belanger, and welcome to Episode 329 the Christmas special edition of the New England Legends podcast.

RAY: And I’m Ray Auger. Happy Holidays no matter what you celebrate, we’re glad to have you with us on our mission to chronicle every legend in New England one story at a time. So many of our story leads come from you. So please reach out to us anytime with your own local stories of ghosts, monsters, aliens, roadside oddities, true crime, and the just plain weird.

JEFF: Just a quick note that we usually bring you a From the Vault episode each Monday and a new episode each Thursday, but Ray and I are taking a little holiday break to be with our families. So the next three in a row will be From the Vaults including new commentary from us. We’ll be back with a new episode the first week in January. We’ll explore the haunting side of this Longfellow poem right after this word from our sponsor.

SPONSOR

[CITY NOISES]

RAY: Okay, Jeff. We’re standing in front of the Longfellow mansion here on Brattle Street in Cambridge.

JEFF: Today it’s a National Park Service site, and it’s also known as Washington’s headquarters.

RAY: It’s a gorgeous estate. It was built in 1759. George Washington made the building his headquarters in July of 1775 and made it the base of operations during his siege of Boston. He moved out in April of 1776. In 1819, the house took in boarders to help keep the family finances afloat. Nathan Appleton bought the house in 1843.

JEFF: Not long after, Longfellow fell in love with the owner’s daughter, Frances Appleton AND with the house and neighborhood. As the young poet eventually got married, his father-in-law gifted the estate to Henry and his bride as a wedding gift. It remained the in Longfellow family right up until 1972 when it was donated to the National Park Service as a museum.

RAY: A lot of creative endeavors happened under this roof. Longfellow used to write on the first floor in George Washington’s former study.

JEFF: That’s for sure. It’s always cool to see the place that produced the art. Including a poem that was turned into a Christmas song.

RAY: I know the song you’re talking about. [SINGS A LITTLE:] I heard the bells on Christmas Day / Their Old familiar carols play….

JEFF: That’s the one. It started as a Longfellow poem. And as with any poem, it began with a story that inspired the art. So let’s head back to 1863 and find that story.

[TRANSITION]

RAY: It’s November of 1863 here in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The United States is embroiled in a brutal civil war. It’s a most troubling time, especially here at the home of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

JEFF: That it is. Longfellow has had a trying few years. It all began two years ago, when his beloved wife, Fanny was sealing envelopes with hot wax. Her arm bumped a candle that caught Fanny’s clothes on fire! Henry rushed to his wife’s aid, but it was too late. She’d been burned badly over so much of her body. She died the next day from her injuries. Henry was also burned in the fire and was too weak to attend his wife’s funeral.

RAY: It was around that time that Henry grew out a beard to cover some of the burn marks on his face. His whole personality changed too. He sank into a depression.

JEFF: By the time the Civil War was heating up, it also took a heavy toll on his heart. Longfellow was an abolitionist. He believed it was important to end slavery. But when his young son, Charley came to his father expressing his interest in joining the Union Army to help the cause, Longfellow told him not to.

RAY: By Charley couldn’t be swayed. Against his father’s wishes, he signed up for military service.

[CANNONS AND MUSKETS]

JEFF: Once Charley’s commanding officer found out who he had in his company, he promoted Charley to Lieutenant. Charley always wondered if his family connection got him preferential treatment.

[WAR SOUNDS FADE]

RAY: By June, Charley had been stricken with a fever. His father traveled to Washington to bring his boy home for the summer to recuperate. Once better, Charley was determined to return to his unit on the front lines. And he was under no misconceptions. He’d already seen shells and cannon rip his friends to pieces.

JEFF: Being an adult, there was nothing Longfellow could do but worry for his son and for his country. Still deeply depressed over the loss of his wife, he found little peace in his work, either. Longfellow wasn’t writing like he used to.

[WAR SOUNDS AGAIN]

RAY: It’s now November. Charley had spent months on the front lines when a bullet finally found him during the Battle of Mine Run.

[MUSKET CRACK]

[MAN GROANS BEING SHOT]

RAY: The bullet entered Charley’s back and came out his shoulder, just clipping his spine. Through a miracle, he survived the attack.

[TRAIN SOUNDS]

JEFF: Longfellow traveled back to Washington to bring his boy back to the family home in Cambridge to recuperate. Unlike a fever that eventually passes, it’s unknown how long these wounds could take to heal, or if Charley might slowly slip away. It’s December 8th when Henry and Charley get home to Cambridge.

RAY: Henry is beside himself with the idea of losing his son. He’d already lost his wife and much of his will to live. His son’s injuries were pushing him to the breaking point.

JEFF: As the days melt away, and December wears on. Charley is showing signs of improvement. By Christmas morning, Henry believes his son will pull through this. He steps outside into the cold morning air and hears an old familiar sound. But today it’s almost like he’s hearing it again the first time.

[CHURCH BELLS RINGING]

JEFF: The bells toll sweetly through the crips morning air. Something stirs inside Henry, and he finds himself racing to his study to put pen to paper.

LONGFELLOW:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

and mild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men.”

RAY: The poem is eventually published in 1865. And that brings us back to today.

[TRANSITION]

JEFF: In 1872 English organist John Baptiste Calkin set the poem to music. Most of the musical versions, like Bing Crosby’s, for example, only use verses 1, 2, 6, and 7.

RAY: So dropping the part about from each black, accursed mouth / the cannon thundered in the south / and with the sound the carols drowned of peace on earth, good-will to men.

JEFF: Right.

RAY: When you hear that verse specifically, it’s so obviously a story related to the Civil War.

JEFF: Right. But take that verse away and it becomes a story of renewed hope Christmas morning. Renewed hope that arrived through the air courtesy of tolling of church bells.

RAY: The song would also be recorded by Harry Belefonte, Johnny Cash, and Andy Williams, just to name a few more.

JEFF: Many people lump this in as a Christian song given the church bells. However, Longfellow was a life-long Unitarian. Not that you can’t be both a Unitarian and a Christian, but I feel like the poem was mainly about the bells. How the sound rang out so pure that he heard them again for the first time.

RAY: And on that day in particular. Christmas Day. Longfellow found hope renewed in the simplest thing. The sound of church bells.

[OUTTRO]

RAY: Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays no matter what you celebrate. We’re glad you spent a small part of your day with us. And that takes us to After the Legend where we take a deeper dive into this week’s story and sometimes veer off course.

JEFF: After the Legend is brought to you by our patreon patrons. This legendary group of people gives us and YOU a present all year-round by contributing just $3 bucks per month. I know it doesn’t sound like much, but if enough of you do it, it adds up to helping us with our hosting costs, production, marketing, travel, and everything else it takes to bring you two shows each week. Plus our patrons get early ad-free access to the new episodes plus bonus episodes and content that no one else gets to hear. Just head over to patreon.com/newenglandlegends to sign up.

To see some pictures of Henery Wadsworth Longfellow, and his Cambridge mansion, click on the link in our episode description, or go to our Web site and click on episode 329.

Again we wish you a happy holidays. If you’d like to get us a present, how about posting a review for us, or sharing our latest episode on your social media. That goes a long way in helping others find us. And the more people who listen, the more stories we find to bring you each week. It takes a community to do this, so thanks for being part of ours. Also, be sure to download our free New England Legends app in your app store!

We’d like to thank Marv Anderson for lending his voice acting talents this week, thank you to our sponsors, thanks to our patreon patrons, and our theme music is by John Judd.

Until next time remember… the bizarre is closer than you think.