In Episode 154, Jeff Belanger and Ray Auger drive to the grounds of the old Fernald School in Waltham, Massachusetts, just in time for a radioactive bowl of Quaker Oatmeal. This is a facility with secrets. Back in the late 1940s a series of experiments was conducted on 74 boys between the ages of 10 and 17 to determine the nutritional effectiveness of oatmeal. The boys had no idea they were human guinea pigs until a declassified document shed light into the dark corners of the Fernald School.

CALL (OR TEXT) OUR LEGEND LINE:

(617) 444-9683 – leave us a message with a question, experience, or story you want to share!

BECOME A LEGENDARY LISTENER PATRON:

https://www.patreon.com/NewEnglandLegends

CREDITS:

Produced and hosted by: Jeff Belanger and Ray Auger

Edited by: Ray Auger

Additional Voice Talent: Eric Altman

Theme Music by: John Judd

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST FOR FREE:

Apple Podcasts/iTunes | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | Stitcher | TuneIn | iHeartRadio | SoundCloud

JOIN OUR SUPER-SECRET:

New England Legends Facebook Group

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

*A note on the text: Please forgive punctuation, spelling, and grammar mistakes. Like us, the transcripts ain’t perfect.

[DRIVING]

RAY: We’re getting an early start on this one, Jeff.

JEFF: We are. The hope is to get to the old Fernald State School in Waltham, Massachusetts, in time for breakfast.

RAY: That sounds good, because I didn’t eat anything yet today.

[DRIVING]

RAY: Oh wow, look at this place! What a huge, creepy, complex of buildings. These old asylums are always freaky.

JEFF: They are, because it’s so easy to imagine what life must have been like here. But this is a facility with secrets. Some pretty dark secrets, too.

RAY: And you said we’re here for breakfast?! What’s on the menu?

JEFF: No menu here, Ray. There’s only one item offered: Quaker oatmeal.

RAY: Not my favorite… unless they want to sponsor us. But I guess it’ll do.

JEFF: Here’s the thing, Ray. I wouldn’t eat the oatmeal at the Fernald School.

RAY: Why not?

JEFF: Because this oatmeal… is radioactive.

[INTRO]

JEFF: Hello, I’m Jeff Belanger and welcome to episode 154 of the New England Legends podcast. If you give us about ten minutes. We’ll give you something strange to talk about today.

RAY: And I’m Ray Auger, thanks for riding along with us on our mission to chronicle every legend in New England one story at a time. And we can’t do that without the help of our patreon patrons. These legendary people throw in just $3 bucks per month to not only help fund a growing movement, but they get early access to new episodes, plus bonus episodes and content that no one else gets access to. You know these stories help connect us, so please head to patreon.com/newenglandlegends so we can connect with an even wider audience.

JEFF: And if you don’t already, please hit the subscribe button on our show, so you don’t miss a thing. We also appreciate it when you post a review, or tell a friend or two about our show. These stories are crowd-sourced more than you know, so the more people who listen, the more who reach out with their own strange local legends, the more we all win.

RAY: So Jeff, we’re heading to Waltham for breakfast?

JEFF: Right.

RAY: But it’s a radioactive breakfast.

JEFF: Right, but what if I told you, “Eat this and you’ll be rich!”

RAY: Rich, but radioactive?

JEFF: Right.

RAY: How rich? And how radioactive are we talking here? Enough to give me super powers?

JEFF: It’s complicated.

RAY: It always is.

JEFF: The Fernald State School was founded in 1848 and was originally called the Experimental School for Teaching and Training Idiotic Children.

RAY: That’s a horrible name.

JEFF: Those were different times. It would later be called the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded after it was located here in Waltham in 1888. During the 1920s, under superintendent Walter Fernald, the facility became the model for the American eugenics movement. At its peak, this facility featured 72 buildings, and 2500 patients on a 196-acre campus.

RAY: Eugenics is an ugly concept for sure. The idea is to improve the overall gene pool of the human population by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior. Once you start judging groups of people as inferior, it’s a slippery slope into pure evil. Ask anyone who’s ever heard of Adolf Hitler.

JEFF: But in 1920, his research was considered cutting edge. So much so that they would rename this hospital the Walter E. Fernald Development Center.

RAY: But eugenics isn’t why we’re here.

JEFF: No, we’re here for oatmeal. Let’s head back to 1945 and figure out how this happened.

[TRANSITION]

JEFF: It’s July 16, 1945, and just about 2000 miles southwest of Waltham, Massachusetts, something very big is about to happen…

[NUCLEAR BOMB GOES OFF]

JEFF: 210 miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexica, the world’s first nuclear explosion has just detonated, ushering in the nuclear age.

RAY: It’s an exciting time, but also a damn scary one too. America now has a super weapon. The ability to end the world if we wanted to. And you can bet your blasting caps that Russia is working on their own bombs, as are other countries.

JEFF: The people in charge of such a devastating weapon have questions.

RAY: That they do. What are the effects of being too close to a blast zone? How long is the area dangerous after the bomb goes off? How much radiation is safe? If kids duck and cover in the classroom, will they survive a nuclear blast?

JEFF: Spoiler alert, they won’t.

RAY: You also have to look at the other side, Jeff. This bomb might actually put an end to World War II. It could mean long-lasting peace not just in Europe and the Pacific, but around the globe. We gotta get this right, and we need to understand this thing from all angles.

JEFF: I get that too. Still, it’s a frightening new world we now live in. Back in Massachusetts, some folks at MIT are trying to get something else right. The thing about radiation, is it’s easy to detect with devices like a Geiger counter.

[CRACKLING OF A GEIGER COUNTER]

RAY: I get it, people are scared, if you’re close enough to the blast you die, if you’re a little bit away from the blast you get horribly sick then die, and if you’re further out then that, you may get sick years later and die.

JEFF: It’s a grim prospect, I know. And staying healthy whether near a nuclear blast or not, is on the minds of a lot of people.

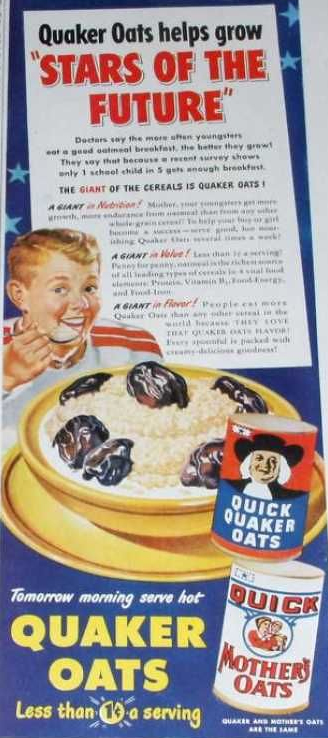

RAY: That it is. Two years ago, back in 1943, the Department of Agriculture produced its first every dietary guidelines. They said oatmeal is an ideal whole grain, and the public is catching on. The Quaker Company has seen sales skyrocket over the last couple of years as more people adopt oatmeal as their breakfast of choice. But… there’s competition in the breakfast cereal market. There’s Cream of Wheat by Farina, plus a bunch of new cold cereals out there all claiming they’re nutritious. But which one is the best for you? Quaker oatmeal wants to make sure they come out on top.

JEFF: The Quaker Company wants to know how their oatmeal stands up as far as getting nutrients into the bloodstream so they reached out to the folks at MIT. MIT devises an experiment, they just need some… uhhh… lab rats.

[CAFETERIA BACKGROUND NOISE]

RAY: It sounds like breakfast is being served here at the Fernald School. The group of boys gathered in this section are members of the Science Club. And being a member has its perks. Like free breakfast! I can see them scooping out the oatmeal.

JEFF: I like oatmeal especially in the winter. Maybe add a little brown sugar, a little milk, it warms you up.

RAY: But brown sugar and milk isn’t the only thing they’re adding to the oatmeal here at the Fernald school, is it?

JEFF: No, it isn’t. The key ingredient here is a secret. After Quaker Oats and MIT put together their experiment, the MIT people reached out to the administrators of the Fernald School and asked for some human Guinea pigs. Robert Harris, a professor of nutrition at MIT, lead the experiment.

HARRIS: What we want to do is expose the test subjects to a low dose of radiation. Between 170 and 330 millirems. Why, it’s about the same as maybe 30 chest x-rays in a row.

RAY: That doesn’t sound so bad… does it?

JEFF: Would you like to give your kid 30 chest x-rays in a row?

RAY: No.

JEFF: Me neither. Still, MIT explains how potentially harmless this experiment will be, and how it’s a matter of national security, national health, and the potential well-being of all Americans. The Fernald School agrees, and the Quaker company supplies the breakfast in the hopes of proving Quaker oatmeal isn’t any worse than cream of wheat when it comes to absorbing iron and calcium into the bloodstream.

RAY: Ahhhh So the radioactive material is like a tracer. Feed the kids the material, then later test their blood to see if it passed through… Let’s head back to the kitchen.

[KITCHEN SOUNDS]

RAY: I can see the cook stirring a big pot of oatmeal on the stove. She’s pouring in milk that MIT has laced with radioactive iron and calcium.

JEFF: How do you even measure something like that into the oatmeal?

RAY: I’m sure they’re following a recipe.

JEFF: Have you ever cooked anything, Ray?

RAY: Sure!

JEFF: If a recipe calls for adding one cup of flour, and you measure perfectly, you pour it into your mixing bowl, and you stir. Are you 100% certain that you mixed the flour so it’s evenly spread throughout all of your batter? That if three or four people were to take a spoon and scoop up a spoonful of your batter at random, they would each have exactly the same amount of flour in their spoons?

RAY: Ohhh I get it. Who’s to say that one kid got slightly more radioactive material than another?

JEFF: Right. One clump of flour in your batter may provide an awkward bite for your cake. A lump in this oatmeal could mean cancer.

RAY: The folks of MIT thought of that too, Jeff, because some of the boys who are part of this experiment are directly injected with the radioactive calcium.

JEFF: How horrible!

RAY: Over the next several years, 74 boys between the ages of 10 and 17 are fed or injected with radioactive material as part of this study. None of them know it, none of them asked for this, and by the time the study ends in the early 1950s, this became the Fernald school’s best-kept secret.

JEFF: Do we know what was learned by radiating these intellectually disabled kids?

RAY: Professor Harris would say it proved Quaker oatmeal is no worse than cream of wheat for absorbing nutrients like iron into the bloodstream.

JEFF: And what about any long-term health effects on these boys?

RAY: Professor Harris explains.

HARRIS: It’s difficult to tell what effects such a low dose of radiation will have on these children. We think an exposed child would have a one in 2000 chance of contracting cancer, which is only slightly higher than the average.

RAY: And that brings us back to today.

[TRANSITION]

JEFF: I have questions. A lot of questions.

RAY: Me too. Let’s get to them!

JEFF: If none of the patients knew, and this was a secret, how did it get out?

RAY: In 1993, the Secretary of Energy declassified several Atomic Energy Commission documents, and that’s when researchers and the media started combing through them. It didn’t take long for someone to realize a grave injustice occurred to these kids at the Fernald school.

JEFF: The Boston Globe newspaper reports on this, urging any of those boys to come forward. In January of 1994, the U.S. Senate investigates these reports, with Senator Edward Kennedy chairing the investigating committee. It’s Kennedy who askes the question: how come this experiment wasn’t conducted on MIT students, or kids from some fancy private school? Why was it conducted on some of the most vulnerable members of society?

RAY: The answer is obvious. Because at the time everyone thought of the boys at the Fernald School as less-than others. They were expendable, and so they became the lab rats.

JEFF: In January of 1998, a lawsuit settlement of $1.85 million dollars was reached on behalf of the surviving boys who were part of this experiment.

RAY: In 1974, the United States passed the National Research Act which was in response to the Tuskegee Study where hundreds of African American men were promised treatment for syphilis as part of a research study. The problem was the study was meant to observe the long-term effects of the disease on soldiers, so no treatment was ever given. Those men could have sought treatment elsewhere had they known they weren’t getting medicine. But Tukegee was just one example. And as more time passes and more documents become declassified, other unethical experiments, like this one at the Fernald School, also come to light.

JEFF: The Fernald School closed its doors for good back in 2014. Looking at these vacant, scary buildings today, I think we should be grateful that sometimes facilities like these give up their secrets, because maybe there’s a chance experiments like these won’t happen again.

[OUTTRO]

RAY: And we STILL haven’t had breakfast.

JEFF: Sorry about that. You maybe wanna grab food somewhere else?

RAY: Definitely not here.

JEFF: I agree. If you enjoy listening to our tales of odd history, ghosts, monsters, and other New England Legends each week, please consider telling a friend or two about us, post a review, and be sure to get more involved. Our Super Secret Facebook group has turned into a fun community of legend seekers. And you can call or text our legend line anytime at 617-444-9683. You can even leave our show closing on our voicemail.

RAY: We’d like to than Eric Altman for lending his voice acting talents this week, and our theme music is by John Judd.

VOICEMAIL: Hi, this is Isaac McDonald from Nova Scotia, Canada. Until next time remember… the bizarre is closer than you think.